What do the British Public think about green protectionism?

Since Britain Remade, the campaign group I work for, launched just over a year and a half ago, we’ve focused our work on the difficulties the planning system causes in building the homes, transport links and clean energy infrastructure that the country needs. We think there’s a bunch of things that the new Government can do to get Britain building again.

But, as well as being pro “building stuff”, we're also interested in how we can ensure the clean energy transition happens in a smooth way for people across Britain - for example how, where possible, tackling climate change happens at the same time as cutting costs for people.

With this in mind, one of the emerging issues is something that we think is best referred to as “green protectionism”.

Over the last year or so, there’s been a rising trend in politics to use protectionism to block the import of new technologies, or the deployment of clean energy infrastructure. A recent example of this is the Biden Administration's decision to put tariffs on Chinese made EVs with the EU following suit.

Given the trend towards this as an approach taken by different governments, we wanted to undertake some public opinion research to understand the British public’s attitude to green protectionism. As such, a few months ago we held a series of focus groups and ran a survey to look at public attitudes to green protectionism in several areas:

Electric Vehicles

Heat pumps

Energy production

Interconnectors

Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism

To conduct this research, we surveyed a nationally representative sample of more than 2,000 people before the General Election. For those that are interested, I’ve included the full method used at the end of this piece.1

I know many readers of this substack will have overdosed on polling during the election, but you can find the full data tables from the work here.

The British public’s baseline views on free trade

Before getting into the nitty gritty of each individual issue, we first wanted to understand the public’s broad views on protectionism vs free trade in principle.

Generally, and somewhat surprisingly, we found a soft preference for free trade, at least in theory, with the public’s views on the merits of protectionism changing on a case by case basis.

For example, when asked whether the Government should prioritise “ensuring UK consumers have access to competitive markets and low prices” or “protecting British companies and introduce tariffs on imported foreign products”, 42% of respondents chose the more pro-market framing, with 32% choosing the more protectionist framing and 26% expressing no preference either way.

However, as you can see below, many voters do not necessarily see a contradiction between supporting global trade and building up British capabilities and investing at home. It’s this tension, which changes on an issue by issue basis, that the rest of this piece will explore.

Electric Vehicles

With the above in mind, the first specific policy area we wanted to test were the public’s views on electric vehicles and protectionism. At present, Brits currently pay a 10% tariff for all vehicles imported to Britain from outside of the EU.

Before checking the public’s policy preferences, we first wanted to check the ownership and attitudes towards EVs of the people we surveyed:

As you can see from the above, while a significant proportion of the UK either own or would consider an EV (45%), the majority of the UK (54%) are resistant to uptake. This is due to a range of concerns they have over EVs quality, battery range and cost.

Anecdotally, we know from discussions we’ve had that many people find the cost of new EVs to be prohibitive. This isn’t surprising; more than 80% of car purchases in the UK are second hand, so until we see a well-developed second hand market for EVs, there will naturally be cost concerns about them, as people are often implicitly comparing the ticket for a brand new (or newish) EV to the decade old petrol or diesel vehicle they would otherwise buy.

But what do the public think the Government’s strategy to trade in EVs should be? When tested, voters were equally split on the strategy which should inform UK EV rollout – showing no clear preference for free trade, or protectionism, with 33% saying that the UK government should reduce “barriers to trade like tariffs on electric vehicles to encourage imports” and 33% saying the UK Government should “protect the British Electric Vehicle industry by introducing tariffs on foreign EVs”, with 34% choosing neither option.

In short, this means that the vast majority of Brits think tariffs on foreign EV’s shouldn’t rise.

While this obviously could change, this shows there is not currently a massive constituency for protectionism on EVs. It is therefore no surprise that the new Labour government has ruled out following the EU or USA in introducing tariffs for EVs.

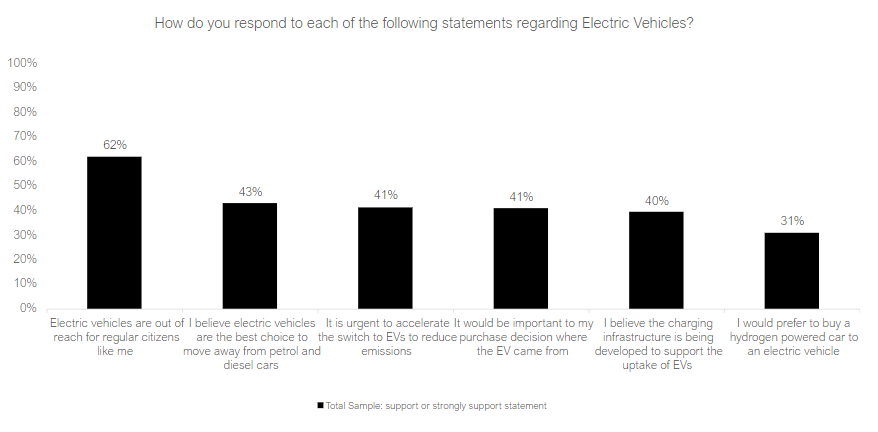

To further understand what drives these views, we gave respondents a series of statements and asked them which they found most convincing.

Below are what people thought the strongest arguments in favour of free-er trade were, with those that backed a free market approach finding cheaper goods for consumers the most credible argument, and those that backed a more protectionist frame finding the argument that free trade is the best way to cut carbon emissions more quickly.

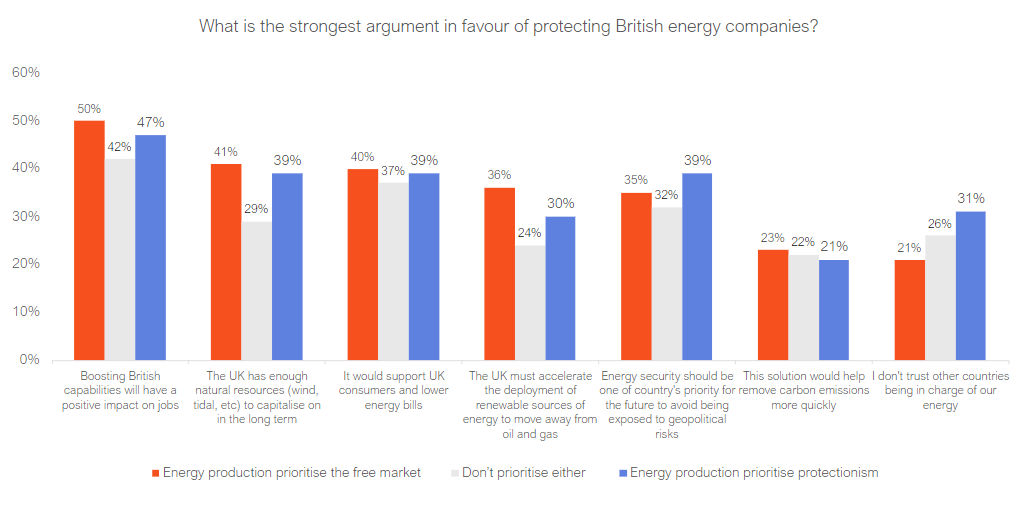

And below is what people thought were the strongest arguments for the more protectionist approach. As you can see, both sides found “boosting British capabilities” and jobs the most credible protectionist argument.

While we know people’s attitudes on trade and protectionism in EVs in principle, we also wanted to test their attitudes on the issue on a country by country basis. It’s clear to us that a lot of the green protectionism we see in policy makers is driven by attitudes to China. But what do voters think?

To test this, we asked a series of questions on people’s views on foreign made EVs from several countries: the UK, France, Italy, Germany, Japan, China and the USA.

As you can see from the below, Chinese EVs were seen as the most affordable in addressing this cost challenge but scored lowest on all other metrics. Conversely, British EVs were considered most trusted.

Given we were particularly interested in attitudes to Chinese EVs, this is something we interrogated further in our focus groups. Broadly, it seems that opinions around Chinese made EVs are split, with those sceptical of Chinese EVs raising concerns about quality and geopolitics, while those who are more comfortable with a free trade approach favouring the cost reductions that trade with China brings, in part because they are used to reliable, cheap chinese goods in other sectors.

Heat pumps

The other consumer item we tested public attitudes to were heat pumps.

For the uninitiated, a heat pump is a method of home heating that transfers heat from one location to another, often from outside to inside a building, using a small amount of electrical energy. Sometimes described as being like a “fridge in reverse”, they can be used for both heating and cooling, making it an efficient alternative to both traditional heating like gas boilers and air conditioning systems.

Under policy set by the last Government, there was a target phaseout date for new gas boilers for most households of 2035. Instead, it was expected that households would switch to heat pumps (and other methods of low carbon heating) to help cut greenhouse gas emissions.

However, during the election campaign, Ed Miliband, Labour’s new Energy Secretary, committed to drop this target, arguing that “we’ve got to show that heat pumps are affordable and are going to work for people.”

This is politically wise. Our polling shows that familiarity with heat pumps is strikingly low, with only 13% of respondents saying they were “very familiar” with them, and only 3% saying they have a heat pump at home. Interestingly, this paucity of knowledge of heat pumps feeds into respondents’ appetite for protectionism, with just 18% of people thinking that the Government should focus on importing heat pumps, compared to 35% disagreeing. It is also worth noting that 47% answered “don’t prioritise either”.

This suggests that while support for a protectionist approach to heat pumps was greater than that for free-trade, this protectionism is less connected to consumer preference, but a broader aspiration we see amongst voters to stimulate British industry. In fact, in contradiction to these findings, our focus groups actually found a slight preference towards taking a more free market approach to heat pumps.

It seems clear to me that most normal people spend basically no time planning to buy a new form of home heating. This, coupled with a very low base level of knowledge of heat pumps, means that opinions on the topic are really malleable, with people retreating to a sort of gut instinct reaction.

This premise was further reinforced when we tested which messages resonated best with each group. As you can see, messages around boosting British capabilities and expanding job opportunities resonated best with those that had a protectionist preference, while the pro-market segment mainly looked to foreign heat pump imports as a way to address high costs.

Energy Production

One of Britain Remade’s main focuses since we launched has been looking at the policy levers that need to be pulled to allow more homegrown sources of energy to be built in Britain.

Generally, we find that people are very supportive of taking measures to build more energy infrastructure here in Britain. In fact, in the case of a new nuclear power, some are even very happy to have it built near them.

One thing we have previously noticed, however, is that this is often coupled with concern about the role that foreign companies play in building much of Britain’s new energy infrastructure. In a world where Orsted are building Hornsea 3 windfarm and EDF are building Hinkley Point C, what do people think about foreign involvement in our energy infrastructure?

Firstly we asked whether people agreed or disagreed with a series of statements:

Unsurprisingly, this finds that a majority of voters are convinced that the UK should strive for energy self-sufficiency and reduce its dependency on foreign trade partners.

We then asked respondents to choose between two options: the “government encourages foreign companies to build new sources of power generation in Britain…” vs the “government prioritises having only British Companies build new sources of power generation in Britain…”. As you can see below, 25% chose the former, while 49% chose the latter.

When we dug into this further, to understand why people thought this way, we found that the main benefit associated with domestic energy production was the prospect of boosting the economy and job opportunities. You can find more on this in the graphs below.

Most interestingly, support for a protectionist position on energy production is consistent across the country, across all age groups, all genders and all political sensibilities. Given the above, it is no surprise Labour had been keen to lead with their new energy company, GB energy, as one of their flagship election manifesto promises.

Interconnectors

Another area we wanted to test was the public attitude to Interconnectors.

Interconnectors are high-voltage cables which connect the electricity systems of neighbouring countries, enabling power to be traded and shared between countries. Interconnectors are generally used when one country generates more energy than it requires for its own needs, allowing them to sell excess energy to neighbouring countries.

Interconnectors have not been without controversy. A proposed link interconnector in Portsmouth, which could provide up to 5% of Britain's annual electricity consumption, has seen some strong opposition, including at one point being blocked by then Business Secretary Kwasi Kwarteng . You can read a bit more about the background to all this here.

But what do voters think about interconnectors? Unsurprisingly, as with heat pumps, awareness of interconnectors is pretty limited, with 68% of those surveyed saying they were not familiar with them.

This lack of awareness was further reflected in their view as to whether government should prioritise interconnectors or not:

As you can see, 48% of those surveyed showed no preference as to how government should approach Interconnectors.

Because of the overwhelming indifference, I won’t go into the arguments they found most or least effective, but you can see them in the full data tables.

Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism

The final area we tested is the public’s attitude to a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM).

For the uninitiated, the CBAM is a form of carbon tax applied to carbon-intensive imported goods. It is designed to prevent "carbon leakage," which happens when production is moved to countries with less strict climate policies to avoid emissions regulations, thereby increasing overall global emissions.

CBAM works by levelling the playing field between domestic and foreign producers. It does this by taxing the difference between the carbon cost applied to the product in its country of origin and the carbon cost that would have been applied if the product were made in the UK. This way, the price of the product reflects the "true" cost of its carbon emissions."

The EU have legislated for a CBAM to enter operation in 2026, and last year the British Government confirmed that they are exploring introducing a CBAM for the aluminium, cement, ceramics, fertiliser, glass, hydrogen, iron and steel sectors. Labour also committed their support to this policy in their election manifesto, arguing it will “will protect British industries as we decarbonise, prevent countries from dumping lower-quality goods into British markets, and support the UK to meet our climate objectives”

In contrast to some of the other areas discussed in this piece, the CBAM is an approach in which many principled market liberals back the introduction of tariffs. In fact, many would argue that a carbon tax like a CBAM is preferable to an approach to net zero which focuses on a hodgepodge of little subsidies, fines and regulations, arguing that it is more cost-effective, efficient and fast, and that any losers from the policy could be compensated through redistribution.

But what do the British public think? Amongst our panellists, 62% of people somewhat or strongly agreed that “It is right that the government put tariffs on products that damage the environment”, with only 10% disagreeing. Similarly, 59% agreed that “the government should use tariffs to protect businesses in the UK who produce more environmentally friendly products”

However, when asked specifically to consider a model similar to a CBAM, this support falls significantly when asked to consider the impact on cost– with the UK pretty evenly split for and against.

When asked to consider the arguments for and against a CBAM,the direct climate benefits of the policy was barely considered by respondents. Instead, both pro-market and protectionist audiences chiefly held carbon tariffs as a way to render British businesses more competitive.

On the other hand, both free-trade and protectionist audiences understand how UK tariffs could adversely impact British exports overseas.

For CBAM, a more abstract concept which we also weren’t able to test in our focus groups, respondents tended to fall back on principled thinking. Ironically, this suggests that market liberal advocates of a CBAM may wish to lean into a much more protectionist way of speaking when trying to sell the policy to the British public.

Conclusion

So what does the above tell us about Brits’ attitudes to “green protectionism”?

I’m wary of extrapolating too much from a fairly limited data set, especially when on some topics the publics’ views are really malleable. It is worth remembering that in almost every question we asked there were a significant number of “don’t know” answers.

That said, I think we can draw a few broad conclusions.

In their hearts, Brits would like us to do more things here in Britain, but when push comes to shove they also care deeply about the price they personally will pay. This means that where they view a policy area as being one in which they personally will bear the cost, then they are much more comfortable with a free market approach.

Conversely, when it comes to things they consider the responsibility of the state, such as energy generation, they much prefer a protectionist or dirigiste approach. This leads them to not only favour building new energy sources in Britain, but in having these energy sources be built by British companies.

Finally, free market arguments for policy are more effective when they emphasise cost, speed, and personal choice; whereas arguments for more protectionist policy resonate more when they emphasise long termism, security and the national interest.

To produce this research, we used a quantitative research approach through an online survey, which gathered insights from a nationally representative sample of over 2000 respondents in the UK. Data collection took place during April 2024 and was conducted via an online survey platform, allowing participants to complete the survey at their convenience within the designated time frame.

Statistical analyses, including descriptive and inferential analyses, were performed to analyse the survey data and draw meaningful conclusions. Weighting adjustments were applied as necessary to correct for any imbalances in the sample composition and to ensure the findings accurately reflect the UK population.

I note al the above is based 100% on acceptance of the AGW hoax.

Bad idea.